2010s

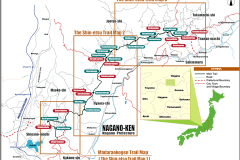

I traveled to western Japan to thru-hike the Shinetsu Trail: an 80-kilometer long trail in the Sekida Mountain range that runs along the border of the Nagano and Niigata prefectures. The Shinetsu Trail (est. 2008) is Japan’s first federally funded long trail, like the Appalachian Trail in the United States.

This summer, I traveled to western Japan to thru-hike the Shinetsu Trail: an 80-kilometer long trail in the Sekida Mountain range that runs along the border of the Nagano and Niigata prefectures. The Shinetsu Trail (est. 2008) is Japan’s first federally funded long trail, like the Appalachian Trail in the United States. In fact, the Shinetsu Trail is partially modeled after the AT. In 2003, four members of the Shinetsu Trail Club visited the United States—by a coincidence of factors, hosted by my family in our home in Dahlonega, GA, just thirty minutes from Springer Mountain at the southern terminus of the AT—to consult with various AT organizations.

My main question going into the summer was to find out the ways in which the AT influenced the Shinetsu Trail. The influence can be broken down into two broad categories: management and philosophy. One of the biggest challenges the club grappled with was how to cooperate different levels of bureaucracy—federal, state, and local—with its non-profit status to form the trail. Trail maintenance was another question of management in efforts to manage a team of volunteers to maintain the trail for most of the year.

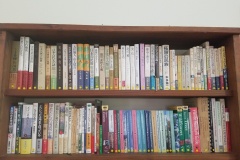

The American environmental philosophy that permeates the AT influenced the Shinestu Trail primarily by one member of the Shinetsu Trail Club, Noriyoshi Kato (1949-2013). Kato was a popular environmental writer and ’05 AT thru-hiker who drove the creation of the Shinestu Trail. His interest in American environmental philosophers like John Muir and Thoreau is evidenced in his books, both ones that he’s written and others that he owns. At the trail club headquarters, one of Kato’s old bookshelves stands. The shelves alternate between books on Japanese history and Japan’s national parks, to Wildflowers of the White Mountains and George Perkin’s Man and Nature. Kato was deeply interested in how American environmental philosophy is applied to conservation efforts through national parks and long trails and sought to apply it in Japan through the Shinestu Trail.

While the Shinetsu Trail does draw from the AT, there are ways in which this trail is unique from the AT. The Shinetsu Trail is deeply embedded in the region through the already existing paths that it was built on. Historical trading routes used during the Edo period brought people from the coast up to the mountains to bring goods including salt, rice, sake, and mulberry material for papermaking. There are also several small shrines along the trail that people have long visited before the Shinetsu Trail was built. A central part of the Shinetsu Trail’s deep ties to people of the region is the satoyama, or “village-mountain”, culture. Satoyama describes the proximity and dependence of local agricultural lifestyles to the mountains.

A major factor of satoyama culture in this region of Japan is its beech tree forests. The forests are several hundred years-old with greyish-white trunks and bright green leaves. I once commented on the prevalence of cedar trees in the area–historically planted for logging–and someone mentioned to me that people don’t like cedar trees so much, partly because they are dark forests. Beech forests, on the other hand, are large but their branches extend outward in a way that lets in lots of light. The shape of their leaves—scalloped edges—collects rainwater that then follows down the branches and directly down the trunk and into their root system. Aside from a few large ponds, water sources are few and far between in the Sekida Mountains. Beech trees, however, can store water, especially from snow melt, that is then diffused down the mountain in a way that irrigates the landscape.

While the Shinetsu Trail does draw from the AT, there are ways in which this trail is unique from the AT. The Shinetsu Trail is deeply embedded in the region through the already existing paths that it was built on. Historical trading routes used during the Edo period brought people from the coast up to the mountains to bring goods including salt, rice, sake, and mulberry material for papermaking. There are also several small shrines along the trail that people have long visited before the Shinetsu Trail was built. A central part of the Shinetsu Trail’s deep ties to people of the region is the satoyama, or “village-mountain”, culture. Satoyama describes the proximity and dependence of local agricultural lifestyles to the mountains.

A major factor of satoyama culture in this region of Japan is its beech tree forests. The forests are several hundred years-old with greyish-white trunks and bright green leaves. I once commented on the prevalence of cedar trees in the area–historically planted for logging–and someone mentioned to me that people don’t like cedar trees so much, partly because they are dark forests. Beech forests, on the other hand, are large but their branches extend outward in a way that lets in lots of light. The shape of their leaves—scalloped edges—collects rainwater that then follows down the branches and directly down the trunk and into their root system. Aside from a few large ponds, water sources are few and far between in the Sekida Mountains. Beech trees, however, can store water, especially from snow melt, that is then diffused down the mountain in a way that irrigates the landscape.

After talking with people for several days, I set off to hike the Shinetsu Trail myself. The trail was a more solitary experience than I expected—between being a trail that certainly has less traffic compared to the AT, and the hot, humid time of year it was, I only ran into two other people, plus a group of seventy elementary schoolers completing the trail on a hiking program. It was my first solo backpacking trip and it had its challenges, both physical and mental, but was a rewarding one. The trail’s environment felt very similar to the deciduous jungle I associate with the southern part of the Appalachian Trail this time of year. And there were some moments of trail magic—one of my favorite AT phenomenons in which food, drinks, or other care packages are left for hikers—along the trail too. At the end of my first full day on the trail, I found a cooler box at my campsite filled with iced lemonade, sodas, and a small notebook titled: “Trail Magic Register”. And though I didn’t run into many people while hiking the trail, I still experienced the generosity of those that I did, like going firefly watching with the owners of a lodge I stayed at later in the trip. It was the best feeling to walk back into the Shinestu Trail Club office headquarters the day I got off of the trail and to immediately be bombarded by questions like “what kind of wildlife did you see?”, “was Section 3 well-maintained?”, and “how are the beech tree forests this time of year?”. I feel a new commonality with people who have hiked the Shinestu Trail and those who live near it in the region.

I cannot thank the Chase Coggins Fellowship for making this experience possible. It has made me grow as both a scholar and as a hiker in ways that I hope to continue to build on by turning this project into my senior thesis for the Environmental Studies major. The existing regional relationships to nature on the Shinestu Trail may contribute to the impression that Japan is a country with deep ties to the environment, adding to the amalgamation of classical haiku about natural landscapes, sixty-five words for green, and pilgrimage trails like the Shikoku Trail. I want to set my thesis against that impression and ask, why then, is the “long trail” concept a new phenomenon, and what does it contribute to their already existing walking culture and relationship to nature? The other question I currently have is about the cross-cultural influence of environmental American environmental philosophers were also influenced by Buddhist texts and other Eastern philosophies. What cross-cultural influences in environmental philosophies have existed over time that have shaped the relationships to wilderness—conservation, recreation, religion, etc.—in Japan versus the United States? And finally, what is driving the current rise of long trails in Japan? What imperatives—economic, spiritual, environmental—draw people to thru-hiking a long trail in the first place, in any of these places around the world? I hope that my research may illustrate the cross-cultural conversations that have been happening between America and Japan around walking outside that has created long trails we know like the Appalachian Trail and Shinestu Trail and will continue to influence new long trails in both places.

I traveled to Beirut to put some of the language skills I acquired in previous studies to work and explore environmental degradation in Lebanon.

photo

Rayan Semery-Palumbo

Fellowship Report

Chase Coggins Memorial Fund

Summer 2019

In the summer of 2019, immediately following my graduation from Yale College, I hoped to gain more familiarity with the Arabic language as well as the Middle East in general. Supported by the Chase Coggins Memorial Fund, I traveled to Beirut to put some of the language skills I acquired in previous studies to work and explore environmental degradation in Lebanon.

My time in Lebanon was really, really incredible. Countless people in my parents’ generation joked (warned?) about Beirut as a disorderly, dangerous, and unpredictable place — perceptions gained from Lebanon’s civil war, which spanned much of their youth. Beirut now, as I experienced it, is thrilling in a different way; the city’s food, architecture, social life, walkability, residents, proximity to great beaches and magnificent mountains, and anything else you might want are endlessly beautiful.

This beauty, like almost anywhere in the Middle East, is tinged with the remnants—physical, psychological, economic—of recent war(s). The region faces crippling levels of displacement, poverty, and state corruption. Lebanon, a country smaller than most U.S. states, hosts millions of refugees, a practice of openness dating back to one of the region’s first mass-displacements following the creation of the State of Israel and continuing to present day with the mass acceptance of Syrians. Poverty amongst these populations and amongst Lebanese themselves is widespread, and the future looks bleak; youth poverty rates often match or exceed the rates of the parents’ generation, and protests larger than any in Lebanon’s history marked the end of 2019.

As is true elsewhere in the world, this political and economic turmoil snowballed into environmental degradation, reaching peak absurdity in 2015 and 2016 during the well-covered trash crisis. Soon after my arrival in Lebanon, it became apparent that this crisis was still central to the Lebanese political and social atmosphere. On Sunday, June 9, a campaign called Save Our Face launched to begin organizing communities towards undoing the damage done to nature sites around the country. The campaign gained its support and followers primarily through social media, where it was called #SaveOurFace, encouraging supporters to make posts of themselves enjoying nature around Lebanon with their hand over their face, to at once express shame (like a face palm) and to express anonymity or togetherness in the movement to clean the environment. Celebrities, villagers, and youth from around the country made Save Our Face appear, in the days leading up to the June 9 clean up day, like a potential turning point for the country. It was a potential sign of hope and change that many had been waiting for, and it was sponsored by the government, perhaps signaling they had finally begun to consider how their policies and laissez faire stance towards business and waste disposal had contributed to this problem.

On the Sunday, I went to the Ramlet al Baida Public Beach on the west side of Beirut, which is known for its accessibility (in terms of location and its low entry fee) to locals in the city. I was greeted by United Nations staff handing out gloves, trash bags, and t-shirts with the Save Our Face logo printed on them. I descended into the beach and found thousands of Beiruties there, with the vast majority out enjoying the beach and few cleaning up. I was, to say it plainly, shocked at the amount of garbage lining the beach.

Every square foot was filled with small plastics, debris, bottles, cans, needles, and seemingly everything you can imagine. I found a group working and asked if I could join. We, a group of 6, proceeded to work with colanders, rakes, and shovels for about 4 hours, and truthfully, I don’t think we were able to clear more than a 3-foot radius of things, on a beach that stretches more than a kilometer. We cleaned and cleaned and cleaned, yet the deeper we went in the sand the more we found. In the purest sense of the word, it was absurd.

I included photos from this event below, and will follow up with a set of two videos demonstrating a colander full of sand scraped from the top of the beach being shaken out to reveal dozens and dozens of individual pieces of trash — bottle caps, fireworks, plastic toy tennis rackets, everything.

All of this was so discouraging and so painful. For the rest of my time spent in Lebanon, I made friends who were able to take me to some of their most favorite and prized landscapes. I visited the Shouf Nature Reserve for Cedar Trees, to a mountaintop lake, to beaches, and to a massive waterfall. Everywhere I went the only thing capable of undermining the country’s natural beauty was the amount of litter and trash that scarred it.

Everyone I spoke to, including the friends I made, families I met, and several activists/experts on environmental management in Lebanon hoped that a better, more cognizant and clean future was in store; they hoped it would come alongside other political and economic changes the country had long awaited — the gradual dismantling of political systems that engrain and codify secularism, the prosecution of greedy political and business elites who have embezzled billions from the Lebanese people to enrich themselves, and the expansion of government services meant to truly, actually service Lebanon, its people, and its environment. Everyone, as is tradition in the Middle East, held hope. The hope was not in their leaders, but in themselves and in the people to create and spur this change.

Just months after I left Lebanon, from the confines of my Oxford dorm, I learned of protests shaking the country. Protests that demanded the very things I heard every day from those I met. Hopefully these protests finally mark the time all Lebanon’s grime is shaken out — from its beaches, waterways, mountainsides, and Parliament.

My time in Lebanon, though at times deeply discouraging and painful, was utterly fantastic, and I could not be more grateful to the Chase Coggins Memorial Fund for enabling this experience. I included photos below and will send the aforementioned videos via email. I , unfortunately, seem to have lost some photos from the latter end of my trip, which included my trip to the south of Lebanon and to a laketop mountain. I would be happy to provide further information on the date, time, and location of any of the provided photos.

Thank you very much. I deeply appreciate your support for this experience. It was nothing short of life changing.

Because these artworks are largely about the land and environment that surround them, the opportunity to experience the desert landscape they occupy was hugely influential to my understanding of them. Ultimately, I found that even experiencing the extreme heat of the desert in August or getting lost on an unmarked dirt road influenced the ways in which I considered the pieces.

This summer, due to the generosity of the Chase Coggins Scholarship, I was able to visit and conduct research at some of the most remote and inaccessible works of art within the history of American art. My project centered around three works: Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson, Sun Tunnels by Nancy Holt, and Double Negative by Michael Heizer. These works, each incredibly significant to the 1960s art movement, Land Art, are located in remote areas of the deserts of Utah and Nevada. Although I have studied images of these works for many years, the experience of seeing the artworks in person was unlike anything I expected. These large-scale sculptures are only accessible after many hours of driving, often over dirt roads, in a vehicle equipped with four-wheel drive. The Chase Coggins Scholarship made my hope to see these sites possible.

This past August, I drove through the deserts of Utah and Nevada over the course of a week. I traveled along hundreds of miles of road stretching between gas stations and small towns, each made up of only a handful of homes. Beginning in Salt Lake City, I drove along the Great Salt Lake, following single-lane highways and then dirt roads, to the site of the Spiral Jetty. There, I walked along the artwork and around the surrounding salt flats for hours. I camped at the site that night and woke before the sunset to climb the nearby hill overlooking the jetty. I also visited the Golden Spike National Historic Monument, located only 16 miles away from the Spiral Jetty, which marks the completion of the first transcontinental railroad.

Following this, I traveled over many miles to Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels and the Bonneville Salt Flats, and camped in a Nevada state forest. I visited Great Basin National Park and toured a large cave system. Each of these sites, which represent various interactions and relationships between humans and nature, are interesting comparisons to works of Land Art.

From here I traveled to Double Negative, an artwork located on the edge of a large mesa in southeastern Nevada. Upon seeing the work in person, I was struck by the dissonance between what I expected of it through my reading and the embodied experience of standing on the edge of the artwork. Following this, I wrote my senior thesis this fall on situating Double Negative within the environmental and cultural history of the region.

I also visited Lake Mead and the Hoover Dam, located 80 miles southwest of Double Negative. At the local Hoover Dam museum, I learned about the history of its creation and its role in the development of the southwestern United States. During my trip, I became increasingly interested in the relationship between works of Land Art and the industrialization and modernization of western America through large-scale infrastructure.

Through the course of this trip, I reflected on works of Land Art in relation to the long histories of the consumption and conservation of natural resources throughout the American West. I also considered my travels in relation to histories of westward travel, beginning with the transcontinental railroad and today continued through the quintessential American road trip. Along the trip, I read Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, similarly set in the desert of the southwest. Because these artworks are largely about the land and environment that surround them, the opportunity to experience the desert landscape they occupy was hugely influential to my understanding of them. Ultimately, I found that even experiencing the extreme heat of the desert in August or getting lost on an unmarked dirt road influenced the ways in which I considered the pieces.

The opportunity to research and experience these artworks and their environments radically influenced my understanding of the works of art, as well as their environments and regional histories. This trip informed my consideration of the role of Land Art works within larger social, political, and economic contexts. It has also provided me with a great amount of insight and clarity as I think about the kind of work I hope to do in the future relating art and the environment. These travels would not have been possible without the generosity of the Chase Coggins Scholarship, for which I am exceedingly grateful.

Soon after I arrived in Tono, I was struck by the realization that the immediate task at hand is to understand why legends were told and written in the first place.

My name is Rayer Ma and I am a recipient of the Chase Coggins Fund in 2017. I proposed to travel to Tono, a small rural town in Tohoku Prefecture in northeast Japan, with the objective of creating a video piece inspired by Tono Monogatari, one of Japan’s most well – known collections of folklore. I am writing today to report to you some results and rewards from my trip.

I would like to start off by s aying the two weeks I spent in Tohoku have been one of the most fulfilling experiences I’ve had as an aspiring artist. Upon graduating from Yale and at a time I was still actively seeking to define my mode of creating, my adventure into some of the most remote corners of Japan led me to surprises I could not anticipate and was only able to interpret after a slow, extensive process of absorption. My time in Japan became an investigation of my purpose and method as an artist and an exercise on critiquing and revising my work.

I departed for Japan with the intention of studying the relationship between virtuality and nature and creating new visual expressions of myth and legends in the contemporary world. Soon after I arrived in Tono, I was struck by the realization that the immediate task at hand is to understand why legends were told and written in the first place. The folklores of Tono Monogatari are full of wild imaginations of strange creatures the villagers both fear and tolerate. But what I took for imaginations are not in fact the products of mere whim. Digging into the history of Tohoku by visiting the municipal museum and library and discussing with my host in Tono, I learned that what the folklores document is a history of poverty and famine. For example, kappa, the supernatural water creature whose cartoon sculptures are installed around town for the tourists, came to being as a way of accounting for missing children sold by starving parents. For those who could not endure both the brutality and shame reality brings upon them , the presence of fantastical and often evil spirits offers a kind of comfort that dwells in the realm of imagination. The supernatural, in Tono Monogatari, can only supersede the natural by reconciling with what nature offers and has taken away . Born out of misfortune, these folklores are means of survival.

I decided to redirect and simplify the goal of my project: instead of performing reenactments of the legends, which I believed was neither adequate or appropriate, I wanted to best immerse myself in the landscape of Tohoku and better understand the relationship it has with its people. It was upon biking out of the humble downtown area and into the rural farm lands, then dismounting from the bike and hiking into the forest as a solo pilgrim in search of the streams, water wheels, and mysterious rock formations described in the legends, that the supernatural forces began to make sense to me. Never have I been in forests so completely dominated by the forest itself: though there were painted arrows a few on the tree trunks, I could tell that I was nowhere near human territory. The silence was heavy and rich against the sound of my footsteps and (bear) bell, and for extended periods of time I felt afraid. At the end of these long hikes, when a giant tear-drop shaped rock appeared before me – or hundreds of moss – covered stones into which ancient portraits of Buddhist monks were carved – the sense of tremendous relief that washed over me did in fact, at that moment, make me believe that I had come under divine protection , that the rocks needed to be worshipped because they daunted me without meaning me harm. It was in part the complete stillness of the rocks that felt calming, as if its persistence in being somehow allowed me to be at peace.

There are ways in which my experience of fear and comfort on a continuum parallels the tension between imagination and reality in the origin of these folklores. Upon consulting with my host in Tono, I left Tono earlier than planned and headed farther north to visit places where the meditation on the human – nature relationship is alive and relevant. I travelled through Miyako, a coastal city largely destroyed in the 2011 tsunami, and spent three nights at a fishermen’s home in Kuji, a small village whose elevation just barely protected it from the giant waves. My final nights in Japan were spent at a Zen Buddhist temple on Chokai Mountain in Akita Prefecture, west of Tohoku, where I befriended Abbot Joko and under his guidance, reoriented myself in my journey towards artmaking. He advised me to cultivate a simple and humble mind, to slow down and learn by observing with patience. To move forward, I must first endure stillness.

Though my direction has changed, the video project was not set aside entirely. Over the course of two weeks, I shot over a hundred videos and three hundred still photographs. Believing that I have gained new understanding of my original subject, I decided to start from scratch and reorganize the grounding principle of the video. Instead of extracting from the narrative of the legends, I want to convey the sensorial field I experienced in the woods of Tono. Since returning to the U.S. I have expanded the project a bit by bringing a few more people on board and working together for the video-in-progress. Taking the episodic form of Tono Monogatari, the video will be a string of short bursts of man-nature encounters in strange, playful, troubling, and comforting ways . Most efforts have been trials and errors, but I am confident that the piece will come together much more mature than I had calculated at the very beginning. In the meantime, I have been working on a series of paintings answering to the question of man – nature relationship using picnic as a conceptual framework (and any finished pieces will be updated to my website: rayerma.com ) . The shapes and colors of Tohoku frequent my imagination.

Again, I want to thank the committee for this incredible learning opportunity. I am extremely grateful for this experience and excited to share my video upon its completion. Without your support, I could not have found myself as grounded and as rich with memory as I am now. Thank you!

Although most residents supported wildlife conservation and recognized climate change as a significant threat, the community held a deeply rooted animosity towards the broader environmentalist movement

I would like to say a huge thank you to the Chase Coggins Fellowship for funding this trip. I learned so much more about the nuances of conservation and it opened up so many questions that I am excited to continue exploring in my time at Yale and beyond. Particularly I am so much more curious about how we decide stakeholdership, how our personal contexts define our relationship to the natural world, and why “environmentalism” as a movement has failed to garner widespread support from local communities. The Arctic Refuge is just one good case study for these, and I am so grateful that I was able to visit and explore. Plus, I met a lot of really interesting people through my interviews, including some that I have stayed in close contact with.

The Many Lives of ANWR

Hundreds of miles above the Arctic Circle, I sat in a rusted-out pick-up truck with my guide Don Burns as he scanned the horizon with a pair of binoculars. He was searching for a herd of female caribou that had crossed over from the mainland the previous night. Barter Island is small—only four miles in any direction—and sits on the edge of the Beaufort Sea, inside the boundaries of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It is connected to the mainland by only a patchy sand spit that traces a jagged arc back toward the horizon. The herd would have crossed here, no doubt trying to escape the dense swarms of mosquitoes that emerge from the thawing tundra each summer. Don parked atop a ridge overlooking the beach and rested his scrawny arms on the dashboard to quell the slight tremor in his hands—the damn Alzheimer’s, he called it. He leaned into the windshield, peering out across the barren tundra for any hint of movement, any dark spot on the horizon that might divulge the location of the herd.

The tundra was bathed in the long tendrils of summer sun, and any caribou would have cast spindly shadows across the surface. Don scanned the expanse of open prairie, meticulously inspecting every ridge and dimple in the earth. Eventually, he froze and turned to me with a crooked smile. “Holy cannoli! There they are, jumpin’ every which way. Must be them damn mosquitoes eatin’ em’ up!” he said as he handed me the binoculars and pointed out past the rounded hills to the edge of the water across the island. I cranked down my window and peered out. Only the faintest hints of movement were visible. It was hard to discern the form of the herd against the dark blue of the water behind them, but they were there. They had gathered with their heads facing into the crisp sea breeze, relishing in the relief it provided from the torment of super-sized Arctic mosquitoes. Their shadows were painted across the tundra in a jumble of sprawling legs and stocky bodies, distorted by the mirage of thermals rising from the earth. I watched for a while as they grazed. Every few minutes, a lone doe would thrash about, throwing off her coat of petulant bugs before sauntering back toward the group with an exasperated shake of her head.

These caribou were members of the Porcupine Herd, a group of more than 210,000 animals that live within the Arctic Refuge and calve along the coastal plain. The herd is a critical food source for residents of Kaktovik, a village on the northern shores of Barter Island, who obtain up to 80 percent of their annual food supply from subsistence hunting. Kaktovik is home to no more than 300 people—mostly Inupiat natives, but with a smattering of military personnel and odd-ball vagabonds, like Don. It is the only permanent settlement inside the section of the coastal plain that was opened to oil drilling in December of 2017 by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—the 10-02 Area. Oil drilling within the boundaries of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge has long been a contentious issue. The Refuge was formally created by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in 1980, which set aside 17.5 million acres as designated wilderness area, but reserved 1.5 million acres of the coastal plain to future oil and gas exploration. In the following decades, a rigorous partisan debate unfolded as representatives grappled with the trade-offs inherent in conservation.

The Arctic Refuge is the largest protected wilderness area in the United States and is home to an incredible array of charismatic wildlife. Wolves, musk oxen, Arctic foxes, and thousands of migrating birds all reside on the fertile coastal plain. When I visited Kaktovik last summer, Don and I spent hours each day driving the length of the island in search of animals—caribou, tundra swans, snowy owls, and if we were lucky, even polar bears. We would drive down one of the two gravel roads that led out from town, tires spitting up a plume of dust. One day, we happened upon a jaeger lilting on the breeze. He was immediately identifiable by his angled, sable wings and soft white underbelly. As we watched, he folded like an origami crane and plummeted toward the tundra to seize an unsuspecting lemming. Seemingly satisfied, the jaeger plucked at the lifeless form, tossing it into the air and catching it again in his beak until he had slashed a small hole in its abdomen and a string of satin innards oozed out. As the jaeger was pulling at this tangle of intestines, a large gull swooped in and grabbed the lemming from beneath him, leaving the jaeger undoubtedly perplexed. This prompted a hearty chuckle from Don, who quipped something about “those rat bastards.”

***

Don is an older man with weathered skin and sunken eyes, but with each guffawing laugh, he reveals hints of a mischievous youth. His dark hair is flecked with streaks of white and his gaunt face is blanketed with a patchy, overgrown beard. He wears the same tattered sweatpants and checkered red-and-brown flannel every day, though they droop from his small frame in solemn defeat. When I first spoke with Don on the phone, he radiated personality. What was supposed to be a quick conversation about my upcoming visit evolved into an hour-long conversation about his family and hobbies. I was planning to visit Kaktovik to learn more about local perspectives on the oil drilling edict and to see some of the wildlife that was likely to be threatened. When I casually asked Don about the caribou, he promised me, “yeah yeah, don’t you worry, you can shoot ‘em with your cameras a’fore we shoot ‘em with our guns.” It was an unsettling prospect, given that I had never so much as killed a mouse before, but he was welcoming and reassuring. Don was originally born in South Carolina, but traveled across the American West until he arrived the oil fields in Prudhoe Bay during the 1980s. There, he met his wife, Nora Jane Kaveolook, who was living in the neighboring city of Barrow. In 1988, they moved 100 miles east to the village of Kaktovik, where Nora Jane was born. They purchased a plot of land in the first and only land sale on the island, and Don built a home from a jig-saw amalgamation of wood planks and raw drywall.

From Don’s house, the whole village is on display. Kaktovik is small, no more than a mile in any given direction. There are no roads, only gravel strips, and all of the homes are built on pedestals. This far above the Arctic Circle, the ground is a patchwork of continuous permafrost, and the seasonal freezing and thawing cycle creates a dynamic topography rife with sinkholes. To combat this, each house is built on adjustable pillars that can be shifted independently to keep the house level. In every yard, scruffy dogs hunker down against the cold breeze, chained up between towers of junk. Rusted trucks, worn tires, and sun-bleached whale bones are piled up in every spare inch of space. On Barter Island, hardly anything is thrown away. All new shipments arrive by barge or plane, which is an expensive endeavor, so the community ethos places a high price on reusing what is already there.

When I visited Kaktovik, Don and I would drive through town every morning, stopping to say hi to everyone we passed. I suppose there are no strangers in a town that small. I asked Don once if he had ever had any problems with other residents in the village. He gave a characteristic chortle and exclaimed, “Honey, I’ been in more bar fights than most people ‘a been in bars!” I took that to mean yes. Don had a gruff way about him, a sort of tell-it-how-it-is mentality that I could imagine got him into trouble sometimes, but he was a warm presence in the community. Don goes out of his way to help the ‘aunties’ and other elders in the village. On one of our daily drives, we were flagged down by a couple of young boys looking for a ride. To this, Don informed me that he practices an open-door policy for all the kids in town because “well you jus’ never can know what’s goin’ on at home.”

***

During my week-long visit to Kaktovik, I stayed at the only hotel on the island, the Marsh Creek Inn. The Marsh Creek has twelve rooms, mostly to accommodate tourists during the whaling season, but when I visited in late July, only 3 were occupied. I flew into Kaktovik on a 9-seater plane, and disembarked at the end of a gravel strip under a large green sign that read “KAKTOVIK REGIONAL AIRPORT” in bold white letters. Only, there was no airport, just sand. I unloaded my bags from the cargo hull of the plane and boarded a school bus that drove me and a shipment of Costco-brand frozen food to the Inn. When I arrived, I was greeted by the manager, Tim, who handed me a key ring and told me not to lose it, because he only had the one. Tim was short, 5’ 7″ at the most. He wore black shorts and a red t-shirt with his high school nickname emblazoned across the back, “Kamikaze.” Tim walked with a perpetual bounce, like he was the star in his very own early-2000s music video. And he always had a joint in his hand.

Inside the Marsh Creek, there was a living room and a cafeteria. The living room was dark, lit only by a single overhead light. There was a worn-in leather couch and two grey Barcaloungers perched in front of a high definition television that was as likely to be playing National Geographic as Fox News. During my visit, I spent hours in this living room playing cards. The summer days were endless and life was slow in Kaktovik, so on days when Don was busy, I spent a lot of time by myself. Early in my trip, I would wander the island in my downtime, becoming acquainted with the layout of the village and exploring the beach; but Kaktovik is small, so I quickly resigned myself to filling the extra hours of daylight with boredom.

***

On one of my first mornings in Kaktovik, I stood on the pebbled shore watching a dense grey fog roll in off of the sea ice. The mist shrouded the village in a churning haze. Each drop of vapor was settled precariously on the brink of freezing—half snow, half water. The town was quiet except for a few kids who ran along the beach casting their fishnets into the sea and the lone red truck, the Polar Bear Patrol, which drove languid circles around the island. I wandered up to Don’s fish camp, a grey shed that contained only two damp cots, a propane torch, and some bear spray, and I clambered onto the roof. From here, I had hoped to catch a glimpse of polar bears or seals out on the towering ice sheet, but the fog blurred the line of the horizon into a dull shadow, and nothing was visible. Instead, I crawled down and walked along the beach toward a one-room plywood shack that sat a few feet above the high tide mark. It was leaden-blue with a red corrugated roof and tin awning. Several picnic tables were scattered around and the floor was cluttered with frayed ropes, scummy buoys, and dozens of Little Tikes toys. When I visited in late July, the shed was empty and quiet, but during the whaling season, it is the epicenter of life in the village—a convergence of captains and cooks and kids.

The U.S. Whaling Convention Act permits the native community in Kaktovik to take three bowhead whales each year to preserve subsistence and cultural traditions. The hunt usually takes place in early September, once the weather becomes cool enough to preserve the meat. Then, the whaling captains set out in small skiffs, weaving silently through the broken ice sheet in search of dark shadows beneath the waves. When a whale is spotted breaking the surface, the captains paddle closer. As a skiff pulls beside the whale, the harpooner stands on the forward bow and thrusts the harpoon into a patch of soft flesh around the blowhole. Modern harpoons are embedded with a small explosive that detonates within the whale, killing it instantly. Once a whale is landed, it is pulled to shore in front of the shack where residents gather to butcher it, piercing the thick black maktak and carving out a square grid of rosy flesh. Traditionally, shares of the whale are divided between the captain and the crew with certain parts, like the flipper, reserved for the harpooner. The remaining portions are distributed to the other residents in town and served at a feast.

After a whale is processed, the scraps are heaped onto a bone pile at the eastern edge of the island. Each fall, this pile attracts as many as eighty polar bears who swim to shore from the ice sheet to feast on the fresh scraps. This massive concentration of polar bears attracts a rising number of eco-tourists. Between 2011 and 2017, the number of visitors to Kaktovik increased from fewer than 50 to almost 2,000. A few businesses have emerged to accommodate the new tourism sector, including a small bed and breakfast and Don’s own wildlife viewing company, Arctic Chalet Tours. The burgeoning eco-tourism industry has generated a significant income for the village, which charges a whopping 12.5% tax on each bed at the bed and breakfast. Still, not all of the residents appreciate the new influx of visitors. Many of the social and spiritual dimensions of Inupiat society are deeply intertwined with the annual whale harvest, and some residents in Kaktovik resent the intrusion of outside tourists on the intimate tradition.

***

Just as the community learns to adapt to the increasing tourism trade, a larger threat looms on the horizon: seismic surveying of Area 10-02 begins in December 2018, another key step toward oil extraction on the coastal plain. Many community leaders have spoken out against the decision, citing the potential threats to subsistence resources and traditional practices, including the annual whale hunt. In an op-ed published in the Anchorage Daily News, longtime resident Robert Thompson wrote, “oil exploration and development would impact my hunting and fishing, and that of other residents of Kaktovik. Hunting is a large part of our… culture, and to take an action that will adversely affect this can be seen as cultural genocide.” Bowhead whales are sensitive to noise pollution, and there is concern that infrastructure from oil drilling may disrupt traditional migration routes and push whales miles offshore, past the reaches of the small whaling skiffs. This infrastructure might also damage the slow-to-regenerate tundra, which still bears the checkerboard scars from thumper trucks that were used to survey the coastal plain in the early 1950s.

For many villagers, though, the most ominous threat is the possibility of an oil spill. This far above the Arctic Circle, dense sea ice and months of darkness would likely render clean-up efforts ineffective or impossible. The sustained pollution would have staggering impacts on the wildlife communities in the Refuge and Beaufort Sea, which would be a devastating loss for subsistence hunters, like the Inupiat, who depend on these populations for survival. Although some proponents of oil drilling in the Refuge argue that an oil spill is unlikely, one need only look 100 miles west of Kaktovik to the Prudhoe Bay oil fields and the Trans-Atlantic pipeline, which have resulted in an average of 504 spills each year since 1996.

Oil and gas development also threatens traditional Inupiat culture. More young adults are leaving Kaktovik to attend college in bigger cities, including all three of Don’s daughters, but as children leave, traditions such as whaling and the native language, Iñupiaq, are lost. The village of Nuiqsut, which is adjacent to the Prudhoe Bay oil fields, was one of the first villages to be transformed by oil and gas development. The Dalton Highway, which runs from Prudhoe Bay to Fairbanks, increased access to health care and education in the village, but it also brought heroin, crack cocaine, methamphetamine, and alcohol. In the years that followed, Nuiqsut saw an increase in suicide rates and addiction. Today, it serves as a cautionary tale for other villages in Alaska. Before moving to Kaktovik in 1988, Don worked at the oil fields in Prudhoe Bay, where he bore witness to the dramatic changes that occurred in Nuiqsut. To him, the prospect of such changes in Kaktovik is cause for considerable unease. Already, there have been several instances of suicide in Kaktovik. “Those boys jus’ get hooked on the booze and don’t think ‘bout what it’s gonna do to they mamas,” he said as he recounted the story of a young boy who recently hung himself in the fire station.

Still, not all the villagers are opposed to oil drilling. Because Kaktovik is so isolated, residents face many challenges. Only one airline—Ravn Air—serves Barter Island, so tickets are expensive and limited, and food and other necessities are disproportionately expensive. At the local grocery store, the Kikiktak Grocery, a gallon of milk costs $8.99, and one of Tim’s famous egg and cheese sandwiches at the Marsh Creek costs $13.50. Moreover, unpredictable weather conditions and months of continuous darkness mean that flights are regularly delayed for up to two weeks. This often makes emergency medical care inaccessible. Earlier this year, for example, a community elder died because the battery on his pacemaker ran out before he could be flown to a hospital in Fairbanks. And to avoid complications, pregnant women are flown out of Kaktovik six weeks before they are due to give birth. Because of these challenges, some residents in Kaktovik support oil and gas development for the promise of new jobs, increased connection to the outside world, and other modern amenities.

Oil drilling along the coastal plain will also undoubtedly generate revenue from dividends and private land sales. Land ownership on the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge is spread across many jurisdictions: private citizens, the Kaktovik Inupiat Corporation (KIC), Ukpeagvik Inupiat Corporation (UIC), the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC), and the U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife. This patchwork of ownership means any companies that choose to lease land for oil and gas development will have to purchase surface use rights from local residents and native corporations. Already, the ASRC has generated $1.3 billion from land leases in other oil fields across the North Slope, and their shareholders receive an average of $10,000 in dividends each year. The prospect of similar dividends from the Arctic Refuge is enticing for many villagers.

Because there are both tangible benefits and critical consequences to oil drilling in the Refuge, most residents are not necessarily opposed to oil drilling, but rather want to see certain conditions or restrictions imposed, such as no offshore drilling during the whale migration or along key hunting corridors within the Refuge. As Dr. Aron Crowell, the director of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center at the Anchorage Museum, notes: “rural native villages… are modern permanent settlements. As such, they have to balance the challenges of modern economic decisions and traditional cultural practices.”

***

Early in the week, while Don and I were searching the island for the caribou herd, he told me that Kaktovik is one of the only places left on Alaska’s North Slope where one can look out in any direction and see nothing but sky. Beginning at the Refuge boundary, just 60 miles to the west, the coast is dotted with oil fields. Point Thompson. Prudhoe Bay. Alpine. Port Barrow. Offshore rigs loom on the horizon, sending pipes full of crude oil out toward expansive gravel fields. Trucks rumble in along the Dalton Highway day and night. As we sat in the car, I asked Don why he moved to Kaktovik. His brow furrowed, then softened a bit as he looked across the tundra. “Camping with six or eight, that’s great and all,” he said, “but nothing beats the solitude. You know, when it’s so quiet you can hear your heart beat.”

I heard an inkling of nostalgia in his voice. Since Don moved to Kaktovik in the 1980s, the village has changed considerably. The North Slope of Alaska is warming at a rate almost twice the global average, and the patchwork of continuous permafrost that underlies the ground is thawing. On our daily excursions, Don pointed out places where the coastline was buckling under its own weight and crumbling into the sea. Broken and cracked, large flakes of sod had cleaved off and tumbled onto the beach. As Nora Jane, the mayor of Kaktovik, noted, “our tundra is melting, that’s our next big problem. It’s happening every summer.” In other villages, coastline erosion has been so severe that entire communities have had to be relocated, which is a frightening concept for residents who were born and raised in Kaktovik.

During the week, I was surprised to find that although most residents supported wildlife conservation and recognized climate change as a significant threat, the community held a deeply rooted animosity towards the broader environmentalist movement. Many people that I spoke with expressed the belief that environmentalists are more concerned with protecting the Refuge as an idea than with preserving the resources for the people that lived there. “Everyone is against oil drilling, but no one asks us what we want,” Tim mused to me one night at the Marsh Creek, a hint of resentment in his voice. It was true. Before I visited Kaktovik, I thought of the conflict over oil drilling in the Arctic Refuge as a black and white question: either we are willing to sacrifice public lands for economic gain or we are not. But after my visit, I had a new appreciation for the subtleties with which the community is grappling. In the face of impending oil and gas development, the residents of Kaktovik are being tasked with reconciling their hope for a better quality of life with their desire to preserve their heritage. To them, the Arctic Refuge is not an abstract concept. It is—and has long been—home.

***

On my last night in Kaktovik, I stood at the edge of the Beaufort Sea. The sun was setting low on the horizon, sinking heavy into the waves. The sky was awash with a watercolor of pale orange, honeysuckle, and lilac. On the horizon, the amethyst peaks of the Brooks Range emerged from the tundra. It was so quiet, I could hear my heart beat.

Soon after I arrived in Tono, I was struck by the realization that the immediate task at hand is to understand why legends were told and written in the first place.

My name is Rayer Ma and I am a recipient of the Chase Coggins Fund in 2017. I proposed to travel to Tono, a small rural town in Tohoku Prefecture in northeast Japan, with the objective of creating a video piece inspired by Tono Monogatari, one of Japan’s most well – known collections of folklore. I am writing today to report to you some results and rewards from my trip.

I would like to start off by s aying the two weeks I spent in Tohoku have been one of the most fulfilling experiences I’ve had as an aspiring artist. Upon graduating from Yale and at a time I was still actively seeking to define my mode of creating, my adventure into some of the most remote corners of Japan led me to surprises I could not anticipate and was only able to interpret after a slow, extensive process of absorption. My time in Japan became an investigation of my purpose and method as an artist and an exercise on critiquing and revising my work.

I departed for Japan with the intention of studying the relationship between virtuality and nature and creating new visual expressions of myth and legends in the contemporary world. Soon after I arrived in Tono, I was struck by the realization that the immediate task at hand is to understand why legends were told and written in the first place. The folklores of Tono Monogatari are full of wild imaginations of strange creatures the villagers both fear and tolerate. But what I took for imaginations are not in fact the products of mere whim. Digging into the history of Tohoku by visiting the municipal museum and library and discussing with my host in Tono, I learned that what the folklores document is a history of poverty and famine. For example, kappa, the supernatural water creature whose cartoon sculptures are installed around town for the tourists, came to being as a way of accounting for missing children sold by starving parents. For those who could not endure both the brutality and shame reality brings upon them , the presence of fantastical and often evil spirits offers a kind of comfort that dwells in the realm of imagination. The supernatural, in Tono Monogatari, can only supersede the natural by reconciling with what nature offers and has taken away . Born out of misfortune, these folklores are means of survival.

I decided to redirect and simplify the goal of my project: instead of performing reenactments of the legends, which I believed was neither adequate or appropriate, I wanted to best immerse myself in the landscape of Tohoku and better understand the relationship it has with its people. It was upon biking out of the humble downtown area and into the rural farm lands, then dismounting from the bike and hiking into the forest as a solo pilgrim in search of the streams, water wheels, and mysterious rock formations described in the legends, that the supernatural forces began to make sense to me. Never have I been in forests so completely dominated by the forest itself: though there were painted arrows a few on the tree trunks, I could tell that I was nowhere near human territory. The silence was heavy and rich against the sound of my footsteps and (bear) bell, and for extended periods of time I felt afraid. At the end of these long hikes, when a giant tear-drop shaped rock appeared before me – or hundreds of moss – covered stones into which ancient portraits of Buddhist monks were carved – the sense of tremendous relief that washed over me did in fact, at that moment, make me believe that I had come under divine protection , that the rocks needed to be worshipped because they daunted me without meaning me harm. It was in part the complete stillness of the rocks that felt calming, as if its persistence in being somehow allowed me to be at peace.

There are ways in which my experience of fear and comfort on a continuum parallels the tension between imagination and reality in the origin of these folklores. Upon consulting with my host in Tono, I left Tono earlier than planned and headed farther north to visit places where the meditation on the human – nature relationship is alive and relevant. I travelled through Miyako, a coastal city largely destroyed in the 2011 tsunami, and spent three nights at a fishermen’s home in Kuji, a small village whose elevation just barely protected it from the giant waves. My final nights in Japan were spent at a Zen Buddhist temple on Chokai Mountain in Akita Prefecture, west of Tohoku, where I befriended Abbot Joko and under his guidance, reoriented myself in my journey towards artmaking. He advised me to cultivate a simple and humble mind, to slow down and learn by observing with patience. To move forward, I must first endure stillness.

Though my direction has changed, the video project was not set aside entirely. Over the course of two weeks, I shot over a hundred videos and three hundred still photographs. Believing that I have gained new understanding of my original subject, I decided to start from scratch and reorganize the grounding principle of the video. Instead of extracting from the narrative of the legends, I want to convey the sensorial field I experienced in the woods of Tono. Since returning to the U.S. I have expanded the project a bit by bringing a few more people on board and working together for the video-in-progress. Taking the episodic form of Tono Monogatari, the video will be a string of short bursts of man-nature encounters in strange, playful, troubling, and comforting ways . Most efforts have been trials and errors, but I am confident that the piece will come together much more mature than I had calculated at the very beginning. In the meantime, I have been working on a series of paintings answering to the question of man – nature relationship using picnic as a conceptual framework (and any finished pieces will be updated to my website: rayerma.com ) . The shapes and colors of Tohoku frequent my imagination.

Again, I want to thank the committee for this incredible learning opportunity. I am extremely grateful for this experience and excited to share my video upon its completion. Without your support, I could not have found myself as grounded and as rich with memory as I am now. Thank you!

Harry Gray

Summer 2017 Project Report

Chase Coggins Scholarship Committee

This summer I traveled to Acadia National Park to explore the sounds of the wilderness. Thanks to the generosity of the Committee, I was able to spend two weeks at a cabin on the west side of Mount Desert Island, the so-called quiet side. From the campground I made day trips all across the island—most of which is national park—to make field recordings. I found enchanting bird songs in the woods, especially the harmonic warble of the hermit thrush. At the top of the highest peak on the island I found two pine trees so close together that they would squeak when the breeze blew them against one another. I recorded the noises squirrels make when provoked to self-defense by the sound of hikers’ boots crunching up the underbrush. I made more than twenty recordings of flowing water—brooks in the woods, mile-wide lakes, the Atlantic at high tide. Sometimes I caught on microphone the conversations of other hikers. On other hikes I focused instead on creating recordings with the instrument I built for the purpose of sonically rendering the natural environment. I walked around with a box that synthesized the dynamics of visible light, spatial orientation, proximity of objects in front of me, and temperature. I created two recordings before slipping and destroying an essential component of the instrument in the middle of the third. I was able to salvage the first two recordings, on which I based the two compositions I have submitted alongside this report, and a few photographs.

Over two weeks in Acadia, I succeeded in attuning my ears to the sounds of the wilderness. My campground was perfectly quiet. I became extremely sensitive to even the most distant hermit thrush. I discovered that its song is different in the afternoon than in the morning. The compositions I created should reflect attunement to even the slightest change in a soundscape. They should also reflect the multifarious composition of a soundscape: some sounds are constant and undulating, while others are brief, staccato, and interruptive. The durations and structures of the compositions reflect my field recordings in that they render, for example, a brief hike through the woods to reach a serene clearing and a lake. Furthermore, I did audio analysis of my water recordings and bird call recordings to create some of the textures for the synthesizers in both compositions. All sounds in the final compositions are synthesized. This was an important choice for me, not to include the recordings themselves, but rather to use information from them to create more pleasing and self-sufficient pieces of music. I had a blast hiking, recording, and composing, and I truly am grateful for the opportunity to have spent so much time in the Maine wilderness. I hope you will hear some of my close attention to nature in my compositions.

Audio compositions:

Exploring the Soundscapes of America by Bicycle

Roommates on wheels

Exploring the Soundscapes of America by Bicycle

Zhengxiang Toh || Angus Mossman

The concept of “wilderness” has fascinated people for thousands of years—in biblical times it was the devil’s playground; the transcendentalists of the 1800’s called it heaven; and today, it conjures up the image of an idealized, untouched landscape. Yet the wilderness as an untouched landscape has drawn increasingly more skepticism. Philosopher William Cronon came to the conclusion that whether or not true wilderness exists today, it “gets [people] into trouble only if [they] imagine that this experience of wonder and otherness is limited to… pristine landscapes [they themselves] do not inhabit.” American poet Gary Snyder put it in these words: “A person with a clear heart and open mind can experience the wilderness anywhere on Earth.”

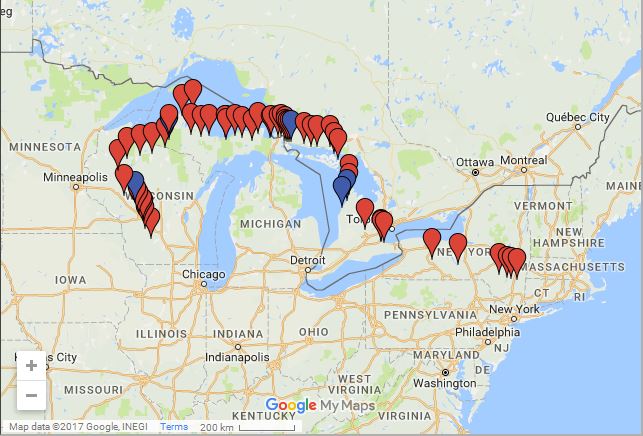

Toh and Angus, partners in crime since Freshman year, set out on a 2000 mile bicycle journey to investigate these questions. Their route took them through a variety of landscapes inhabited (or not) by an enormous variety of people–from the industrial shores of Hamilton, ON to the forested peaks of the Catskills, and from Syrian refugees to Evangelical car mechanics. Through sound recordings, Toh and Angus explored aspects of wilderness that exist in the heart of large cities and vice versa. Then, to see how people fit into the wilderness question, Toh and Angus talked with locals along the way and recorded snippets of their daily lives in their surroundings.

See more at our website Roommates on wheels

In August 2015, I started apprenticing with Khet Chaikam (เกตุ ไชยคำ), a craftsman from the North of Thailand, to learn the craft of traditional musical instruments from Northern Thailand.

Crafting a Sound from Northern Thailand

by Lamtharn Hantrakul

I took a year off, after graduating from Yale University in 2015, to pursue research projects back home in Thailand. In August 2015, I started apprenticing with Khet Chaikam (เกตุ ไชยคำ), a craftsman from the North of Thailand, to learn the craft of traditional musical instruments from Northern Thailand.

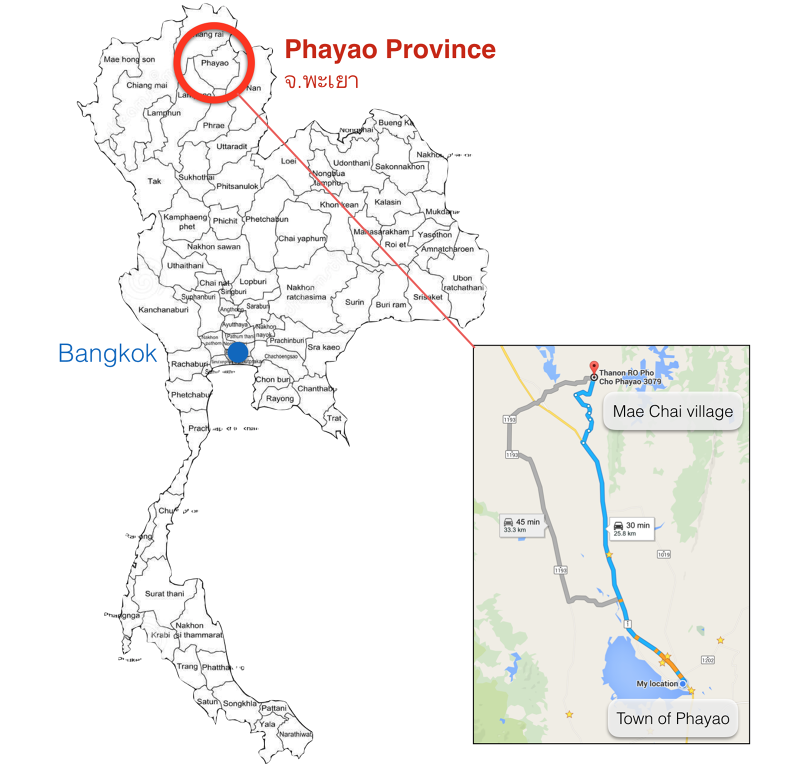

The project took place in Mae Jai (เเม่ใจ), Phayao Province (จังหวัดพะเยา), Thailand.

***

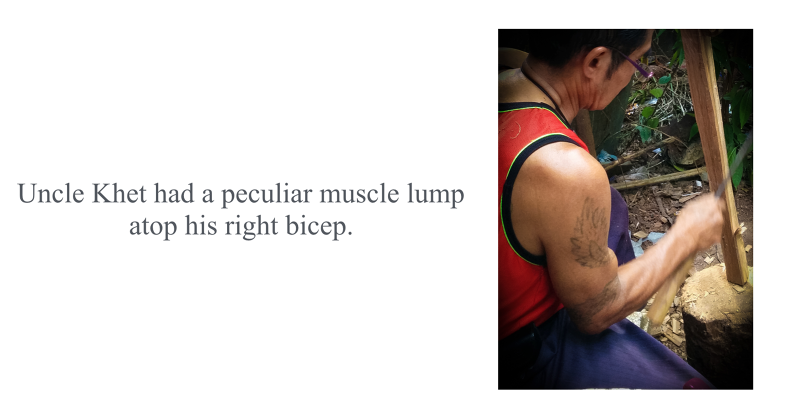

On top of the lump, the tail of a tattooed naga waved in sync as he raised his jungle machete to strip the bark off a pile of logs.

His woodshop is located in Mae Jai (เเม่ใจ), a village located approximately 25km north of Phayao, my mother’s hometown in the North of Thailand. Mae Jai is a sweet name, translating directly to Mother of the Heart. Google Maps Pin

Every morning, I biked down to the morning market in Phayao (พะเยา) to catch the 8AM departure to the Mae Jai market on a modified pick up truck known as a “songtaew” (สองเเถว, literally – “two rows” of passenger seats).

I was always the youngest rider—most were 40 to 60-year-old ladies from Mae Jai who arrived as early as 5AM in Phayao to sell home-grown vegetables, home-cooked curries and sugar-cane sticky rice.

About 20 minutes into the ride, I hopped off the freeway and biked 7 km further into the village to begin my apprenticeship with Uncle Khet at 9AM. The path to the workshop alternated between village houses—some built with wood and corrugated iron roofs and others made from concrete—and rice fields; huge green expanses of rice fields.

It was the monsoon season when I began in August (2015), which meant if it had rained the night before, my bike ride became a dive through the fresh and magical scent of rice stalks frolicking in the morning dew.

Uncle Khet’s house in Mae Jai and his wife.

For over 15 years, Khet Chaikam, 59 – or as “Uncle Khet” as I called him – has been chopping, sawing and carving wood to produce two musical instruments from the North of Thailand: the guitar-like “Seung” ซึง (left) and the fiddle-like “Sloh” สะล้อ (right).

Uncle Khet insisted we begin the apprenticeship on a Sunday, not Saturday, since the Thai word for Saturday (เสาร์) auspiciously coincided with an unlucky astrological sign (ดาวเสาร์ – Saturn).

On the first day, my mother and I prepared a silver plate with a of variety fruits, incense sticks and auspicious leaves. In Thai, the name for the leaves “Bai Khosohn” ใบโกศล is synonymous for good luck and wellbeing. They were for the “Yok Kan Tang” ยกขันตั้ง ceremony, a rite of passage in Northern Thailand when a student wishes to learn from a teacher. The exchange included a sum of 2000 baht (about 60 USD), a purely symbolic token and not to be confused with materials costs or “tuition,” which in Northern Thai culture, is completely separate.

Once finished Uncle Khet finished his blessings for my luck and success, we immediately began with the most difficult part of the process: carving the shaft on the carpenter’s lathe.

It takes Uncle Khet a short 5 minutes to fluidly carve and sand down a shaft. To carve the straight ridges, lotus buds and other ornamentations on the shaft, Uncle Khet demonstrated the different angles of attack on a carpenter’s “straight gauge” (the tool he is holding). To carve out large sections, the “U” of the straight guage points directly at the log. To carve out straight edges, the U is tilted. Pushing the straight gauged while resisting the downward rotational force takes a surprising amount of effort! Naps in the afternoon soon followed.

My first few runs were terrible; I kept fearing an irreversible error. The ridges on my first attempt were not 90 degree steps but shy little bumps, the proportion of my lotus bud was too top heavy and in some locations I had pushed the straight gauge too deep. “This shaft will snap under tension” commented Uncle Khet.

By the end of the afternoon, after cutting through six more logs, my shirt was draped with curls of wood chips. But after about three days on the lathe, I became much more confident using the straight gauge and could make perfect 90 degree cuts. Quite frankly, it’s an oddly satisfying feeling to make right angle cuts on a spinning log.

Later in the week, Uncle Khet and I glued polished coconut shells to a thin piece of wooden board. Uncle Khet uses dried banana tree stalks to tie the components together for two reasons. Firstly, it is cheaper than man-made elastic bands and secondly, the stalks expand when soaked and contract when dry, naturally pulling the coconut and wooden board tightly together.

In the countryside, where raw materials are naturally abundant, it is often cheaper to use a DIY solution than an industrialized tool. I remember Uncle Khet saying “wood will never run out”, which was a little concerning given current environmental trends.

The DIY tools and safety in Uncle Khet’s workshop would have made folks at the Yale Center for Engineering, Innovation and Design (CEID) pull their hair out. Uncle Khet’s disc sander was made from a refrigerator motor bolted to an old, heavy log. Sandwiched between the two were a pair of old sandals, used to absorb shock and vibrations. You turned it on by plugging into a socket extension that sparked every time the disc sander was connected. I was always worried the pile of woodchips on the woodshop floor would spark on fire one day.

Uncle Khet was a nationally recognized craftsman of traditional instruments from Northern Thailand. OTOP stands for “One Tambon, One Product”, a government initiative to support local crafts and produce across Thailand.

At noon, I would sometimes join Uncle Khet for lunch. My favorite food from the North of Thailand was sticky rice (ข้าวเหนียว) and a chilli dip/paste (นำ้พริก)

With our stomachs filled, both Uncle Khet and I rested and napped on hammocks for an hour after lunch before continuing until about 4:30pm to leave time for the return bike ride.

My two best fiddles after 3 weeks of apprenticeship. Since Uncle Khet communicated with me exclusively in Northern Thai, I also learnt how to speak a little bit of it! (อู้กำเมือง!)

After the apprenticeship, I learnt that every country in East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East has a variation of the fiddle, each using different materials to achieve distinct timbres. Thai’s use cow skin, the Japanese use cat skin, the Vietnamese use lizard skin while the Iranians use fish skin. My first hand experience of building fiddles with Uncle Khet inspired me to engineer a cross-cultural modular fiddle system called fidular. This part of the project, lasting from September to December, is documented in detail on my research portfolio site.

In February 2016, I returned to Mae Jai to show Uncle Khet the first prototype of my modular fiddle and get his feedback. He was excited, telling me immediatly “this is great, you can play many different styles and sounds with just one shaft”. Uncle Khet assured me I could sell it as a product and maybe “even make it on television!”

I took fidular and my experience building fiddles to a “Maker Faire” (invention fair) in the northern city of Chiang Mai, the second-largest and most popular city in Thailand after Bangkok. The faire was open to the public and attracted locals, students and teachers from neighboring villagers and the Maker scene in Chiang Mai. The project garnered a lot of interest among fair-goers, especially from a teacher hailing from Mae Sai (เเม่สาย) who said “students in my village aren’t interested in traditional instruments anymore, but maybe your combination of 3D printing and woodcrafting in this new instrument can re-invigorate their fascination”

In January 2016, I keynoted the SEASAC (Southeast Asia Student Activities Conference) Festival themed “Past Present Future”. The conference brought together over 150 students from over 10 international schools in Southeast Asia for 3 days of workshops and activities held at Bangkok Patana School, Bangkok, Thailand. In my keynote, I spoke about the convergence of science, art and culture in the creation of new technology. It was a talk inspired by my experience combining the craftsmanship skills learnt from Uncle Khet with Engineering techniques I had learnt from Yale and is available online.

In March 2016, I was invited by Thailand’s National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to present at a National Science Fair Competition open to high schoolers, college students and professors. My talk, entitled “The convergence of Science, Art, Culture and Commerce”, focused on the merging of traditional technologies like wood carving and weaving, with cutting-edge technologies like 3D printing, in designing new inventions optimized for cultures in Southeast Asia.

As we move into the 4th industrial revolution, I believe we can merge new tools like 3D printing and Artificial Intelligence (A.I) with traditional technologies like wood carving, embodied by locals like Uncle Khet, to develop a new kind of “culture-aware” technology. Too often, traditional cultures have difficulty catching up with new technologies because, unfortunately, no one makes connections between these two worlds.

“Culture-aware” technologies are optimized to integrate with cultural techne (“craft”) and episteme (“knowledge”), particularly those from non-Western traditions. I believe intelligent systems based on Western and non-Western cultures will make technology more robust and better for all users; from all cultures.

My apprenticeship with Uncle Khet, development of fidular and interactions with locals, craftsmen and technologists from my home region have formed the foundation of this vision I hope to refine and implement in the future as I continue onto my Masters and PhD.

The apprenticeship and project was partially funded by Yale University’s Chase Coggins Memorial Fund, under the the objective “traveling to rural areas or developing countries to document and study those regions from a variety of perspectives (including natural or cultural history, health, anthropology, linguistics)”. I would like to thank the Chase Coggins board for giving me this wonderful opportunity.

A three-month experiment in which I construct a teardrop trailer as I tow it across country

Harper Keehn

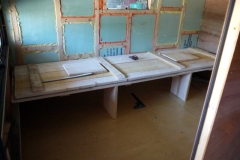

This is an application for funding of a three-month experiment in which I construct a teardrop trailer as I tow it across country. Throughout, I’ll build off of feedback loops that develop over time instead of plans developed ahead of time: this structure will grow around thousands of conversations, miles, degrees of temperature variation, roadside failures, available materials, unforeseen pleasures and frustrations, etc. It will be self-consciously permanently unfinished. In this way, the various work I produce along the way—the trailer itself, of course, but also the documentation and things I leave behind—can be seen as the residue left by a project that is more performance than design exercise. In all, the three functions of this project are (1) the construction of a sculptural object over time, (2) an architectural research question about minimum standards for a functional dwelling, and (3) a literal vehicle for returning to and learning from a vernacular building style that has inspired my last five years of work.

Ostensibly, this project is structured around visits to three ranches managed by friends in Montana, Colorado, and New Mexico. Before this, in New York, I’ll work full-time to build the trailer just to a point where it’s road-legal, safe, and I can sleep in it. Then, over the course of the trip, I’ll borrow shop facilities and use the tools and materials I can find (or bring with me) to continue construction. The trailer will be a scaffolding for incremental and direct design of all scales—all the wonderful marking and fiddling of an animal in a burrow as much as the comparatively big structural decisions of a human building a tiny and waterproof house to whiz down the interstate.

But to say it clearly: this project is exciting to me (and hopefully worth funding to you) not as a novel way to get to Montana. Rather, this is a point of entry into a now-century-old conversation (or really, constellation of conversations) that precedes me: the dignity of craft in the Arts & Crafts revival, the encounter with material as wellspring of design in the early Bauhaus curriculum, the unfinished and contingent quality of Kurt Schwitter’s “Merzbau” and Umberto Eco’s Open Work, Rirkrit Tiravanija’s social “sculptures,” the current architect Kiel Moe’s work on thermodynamic cycles in architecture. These movements feel important but are still maddeningly theoretical to me, devoid of visceral reality. So this is first a personal investigation, because in order to enter that conversation in a meaningful way, I need my own rich experiential data. For this reason, I’m proposing to build a living space by living in a space. To let my hand be forced, for a few months. Although the prospect of this project fills me with joy and rabid excitement, I believe it to be the most serious work I can do, right now.

ii. Details

I expect this to be a full summer commitment. One month of preparation at my shop at home in New York, and two months for continued construction and travel. Although this is an ambitious project, I believe it’s plausible, given my construction experience and willingness to rely on a network of experienced advisors.

I understand the risk of a project that is going in this many directions. As I said, this is: (1) a slow and unfinished sculptural object, as well as (2) a specific research foray into the possibilities of minimal functional housing, as well as (3) a probe to send into a vernacular building style that already does much of what I aspire to do. I’ll describe each of these particular ambitions in more detail below. However, I hope to demonstrate that, in total, this project advances the central effort of my practice.

If this central effort needs a title, I would call it a “material ethics”: how can I treat any and all material that I work with—whether shoveling snow, or building a hay barn, or learning to crochet little hollow sculptural forms—with equal dignity and pleasure? Whether the tools in my hand are familiar or not, I want to practice care as a quality that exists in making, apart from the specific content and technique required by the project at hand.

This is not to imply that others design in a way that is careless or undignified. Rather “care” and “dignity” are, for me, shorthand for a specific kind of honest, stupid, direct effort: a willingness to work like a committed novice even as we become practiced. Being ready to weather frustration and episodic uncertainty, to suffer black eyes and frigid roadside breakdowns, to give myself and the object time and room, and to offer myself as a test guinea pig as I go through the inevitable reams of failed rough drafts. Treating things with care and dignity allows them to be ugly and broken for a while, and requires that I stay right in there with them. I want to be an executor who makes careful and sturdy (and for that, beautiful) internal decisions, in whatever time and form it takes. This, so that I might step back at the end and look at what I’ve just made with surprise and pleasure, but trust that it really will do what it intends to do because I’ve seen all the guts. Or, maybe it’s a flop. But at least it is a record of real effort, a rich journal entry.

As examples, I’m submitting some work that exemplifies this particular push. Objects with a clear purpose delight me because they make this kind of design much easier. Make a spoon, make this tower stand straight on uncertain ground, make a gauge for determining the size of knitting needles. That’s enough direction! Just working through any project like that, with the materials and tools available, is a beautiful challenge. The first attempt pulls a special effort out of us, and I love the honest and halting missteps that are recorded when we have a go at a defined problem with new tools.

However, I think the clearest explanation of this kind of making is the non- functional things I’ve made. I’ve included images of a series of hollow forms that I’ve been working on for the last 6 months. The process of making each of them is the same: I know from the outset that they will resolve into a hollow freestanding shape about the size of a grapefruit, I have a material in mind, and I have a jointing strategy. For instance, steel plate was cut, formed, welded, and polished. Light ochre yarn was crocheted and stuffed with roving. Clay was rolled out, sliced, and slipped together. Leather was cut, tabbed, and glued. Each takes between three and twenty hours (always longer than I expect). While working on them, I lose track of the final form. I focus entirely on figuring out how to make the joint strong and clean, and I get to simply enjoy rolling around in the material properties of whatever I’ve chosen to work with. Eventually, it closes up and I can step back and work on some polishing and refining of the whole form. But critically, I can never predict the end shape from the outset. My plans are immediately frustrated by how the material moves, as soon as I start. These little shapes are the opposite of drudgery, always teach me something about the material and technique, and inevitably show my hand back to me in a way that’s both humbling and gratifying. They immediately suggest a next project. I can give them away without explanation.

(1) As an object:

The trailer is the next scale of this kind of thinking and making. Its material palette and ambitions are more complex, but it requires the same effort. That is, in my descent into the material reality of grappling with functional requirements, it will become an open sculptural object that I can crawl inside and pull down the road at 70 mph. I want it to be sticky with memorable touches, a palimpsest of failure and revision.